As I told a panel at the Poynter Institute, journalists are steadily losing the benefit of the doubt from news consumers

CBS’ decision to publish transcripts of its interview with former Vice President Kamala Harris for 60 Minutes feels like a watershed moment for media in the modern age. And not because there was any editing trickery revealed once the transcript was made public (there wasn’t anything other than typical editing for time and clarity).

I’m also not torn up about the precedent of releasing unedited, raw versions of interviews, though I understand why news outlets like CBS and NPR resist the practice — for fear of revealing material which doesn’t meet their standards of publication, or which is required to remain confidential, among other reasons.

What worries me most — beyond the fact that CBS’ decision came after a request from the Federal Communications Commission which involves the government investigating news coverage decisions — is how the public pressure to release the footage reveals how much trust big media outlets have lost:

The public increasingly doesn’t give reputable journalism outlets the benefit of the doubt when it comes to editing interviews fairly.

And that work – deciding what is news and what is not, what belongs in a news story and what should be left on the cutting room floor – is at the heart of what traditional journalists do.

This is a concern I raised earlier this week while appearing on a panel convened by The Poynter Institute for Media Studies on the challenges to fact checking. I serve on the National Advisory Board for Poynter, which has become one of the biggest names in the world of fact checking journalism and media messages as home of both PolitiFact and the International Fact-Checking Network.

It became obvious, as our conversation progressed, that we were talking about an assault on a wide swath of mainstream journalism including fact-checkers — in which some assert those trying to vet facts are somehow biased, misleading or actively deceitful, often without specific proof. Some of these attacks come from people acting in bad faith, pushing lies or exaggerations of their own to try and delegitimize organizations they know will debunk their propaganda and misinformation.

That’s why I argued journalists need to talk more about how we do what we do, so people can see that turning big scoops and breaking big stories isn’t a magic trick – it’s the result from lots of research, fact-checking, interviews and judgement calls. And the vast majority of journalists I know work hard in good faith to try and make the best decisions they can every day.

https://instagram.com/p/DF-k6jTRXfw/

As I noted, such transparency “won’t necessarily convince the people who are dead set in their belief that we are fraudulent. But there’s all these other people watching this. It’s a schoolyard fight in a weird way. There’s all these people watching it go down, and what you’re really trying to do is convince them of what you’re doing. Because the people who are coming at you, many of them, their critiques are not even fair. They’re not evenhanded. But there’s a bunch of people watching from the sidelines saying, ‘Okay, well, is this true?’ And you’ve got to do something to show them that it’s not, or that you handled it ethically, or that even if you did make a mistake, it was an honest one.”

In today’s conflict-based media environment, failure to push back against an attack is often taken as admission the attack must bear some sort of truth. Also, I’m convinced there are loads of people in our audiences who also believe in the value of fact checking and journalism and they are desperate for those of us who work in this space to defend these basic values.

I don’t know how to reach people so steeped in the propaganda of some outlets that it is tough to agree on basic facts. No doubt, it is comforting to be immersed in media which reflects your cultural viewpoint back to you continuously, regardless of the facts in a given situation.

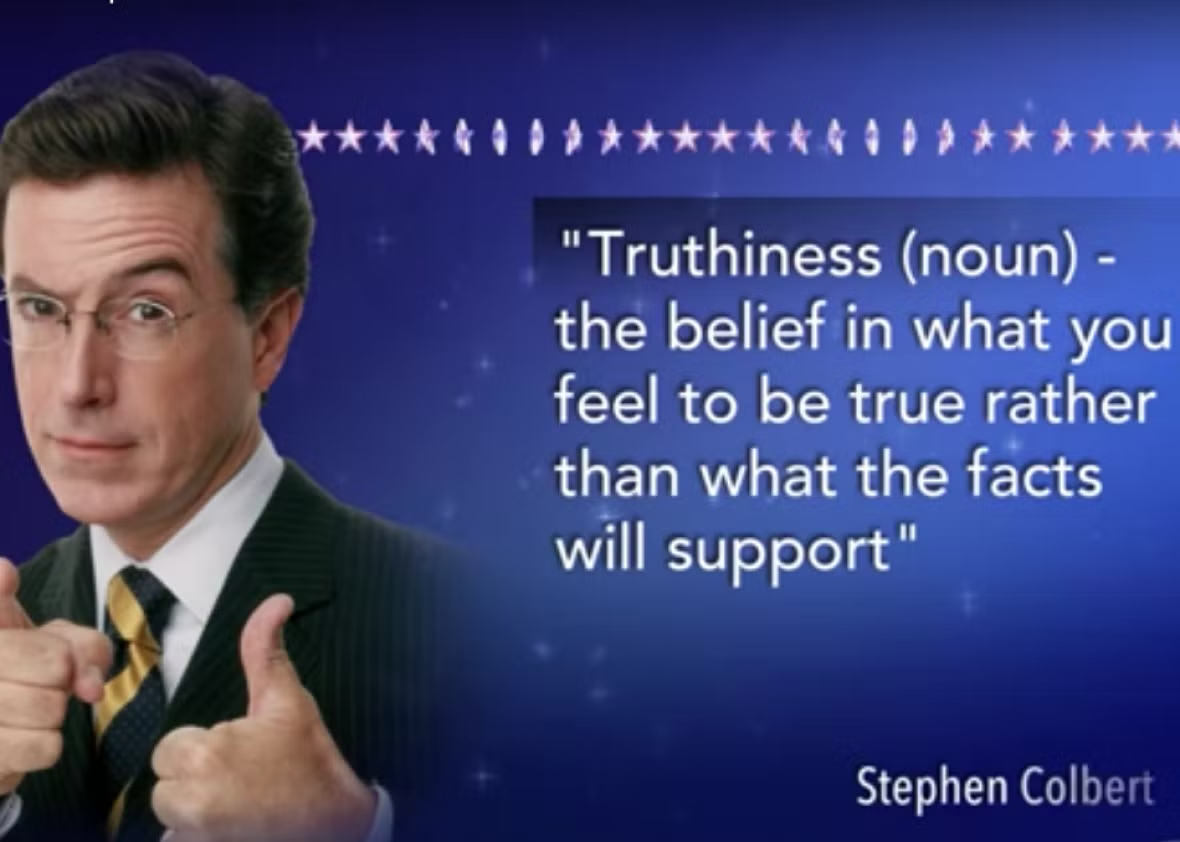

But there is a price to be paid for this propaganda, as I noted: “I think one of our biggest challenges is the growth of what Stephen Colbert called “truthiness,” where people increasingly (think) that because they believe something intensely, it must be true. And we’re now in a political system where some people are trying to make that a reality. But the problem is, eventually, you come up against actual reality, right? So I think that’s our argument (for facts). If you were too trapped in your point of view, then you start to lose sight of how to create vaccines that might cure cancer. How to advance the science that might deal with climate change. We have to sort of deal in facts, or eventually, we lose control of these things that are outside of our belief systems that are rooted in real things.”

And, of course, traditional media can be tremendously disappointing. Like any institution, journalism and journalists can make mistakes, fall into bad habits, indulge excesses, value access over truth telling, and much more.

But those who value freedom of speech and fact-based public discourse can’t afford to turn away from the good in pursuit of the perfect.

And journalists ourselves need to wake up to this crisis.

I remember sitting on a journalism panel about a year and half ago, surrounded by people much more accomplished than I. As I heard complaints about traditional media pile up – some well-founded, others not so much – I had a nagging feeling that we were missing the point.

“Our biggest problem,” I remember saying, “may be that, even when we get everything right, there are a lot of people out there who still won’t believe us.” I met a lot of skepticism from my fellow panelists on that one.

But here we are, at a time when the Associated Press is finding itself barred from press conferences for declining to fully adopt the term “Gulf of America.” Other news organizations have been kicked out of offices in the Pentagon while media platforms mostly friendlier to the Trump administration’s message have been given space. And some big tech platforms which once supported the effort to curb disinformation and misinformation online – Meta and X, I’m looking at you – have walked away from the idea while dropping misinformation of their own about how fact checking has worked.

And now, we face a world where people have access to more information than ever and fewer tools to properly process it — making it tougher for journalists to watchdog the powerful and maintain the principles of free speech which keep democracy intact.