I can’t shake the feeling that the TV industry is lurching back to the bad old days of minimal representation and systemic marginalization

Looking at two different, recent covers of The Hollywood Reporter featuring its roundtable interviews with notable actresses from successful TV dramas and comedy, felt a bit like peering back in time.

Each cover features six actresses – one group from drama and one from comedy – who star in series expected to be awards contenders this year. And each group features just one non-white person: Shrinking co-star Jessica Williams in comedy and Grotesquerie’s Niecy Nash Betts in drama.

It reminded me of the bad old days more than 10 years ago when I complained to the then-editor of THR, Janice Min, about the lack of diversity in its panels of actors and actresses from films considered Oscar contenders. Back then, Min contended there weren’t enough films featuring non-white people in major roles, passing the buck to the industry.

That’s not a serious argument these days, especially in television. Uzo Aduba has given the performance of her career as the lead of Netflix’s The Residence, while other non-white actresses worthy of inclusion are Zoe Saldana (Lioness), Michelle Buteau (Survival of the Thickest), Angela Bassett (911), Ayo Edebiri (The Bear) and Abbott Elementary’s Quinta Brunson, Janelle James, Sheryl Lee Ralph. (It’s worth noting, Nekesa Mumbi Moody, a Black woman, left The Hollywood Reporter as co-editor-in-chief in November.)

So what gives?

The systemic forces which marginalize and erase certain types of people in American life are constant, persistent and ever-evolving, like a virus. They are often enabled by people who feel, in their bones, that the proper position of pop culture in this country is white centered, particularly when talk turns to excellence or achievement.

The current backlash against diversity, equity and inclusion led by the Trump administration just makes these forces stronger. Interestingly, even anti-DEI crusaders know that openly advocating racism doesn’t work in modern times. So, instead, there is a persistent argument that making room for marginalized people requires some sort of unfairness – lowering standard of excellence or improperly boosting people from marginalized groups.

The goal here by DEI critics is simple: to destroy or co-opt the moral authority that civil rights and diversity movements have had in recent decades. In this scenario, critics of diversity can claim they are advocating for fairness, when what they’re really implementing is a return to those bad old days when allowing one person from a marginalized group on a magazine cover was good enough.

Carla Hay wrote a bracing story for the National Association of Black Journalists’ news website noting a long list of TV shows centered on Black characters which have been cancelled or will end this year, including Clean Slate (Prime Video), The Equalizer (CBS), Found (NBC), Harlem (Prime Video), How to Die Alone (Hulu), and The Irrational (NBC). Others, like CBS’ The Neighborhood, will end in the coming TV season.

There’s other troubling signs: A study by Samba TV found the diversity of non-white lead characters in shows dropped 7 percent from 2023 to 2024. A study by UCLA found that, even though streaming TV audiences are more female and want more diverse program topics, television showrunners, creators and lead actors still tend to be “predominantly white and male.” The Ankler noted an even steeper drop for TV shows with LGBTQ+ themes and characters, down 36% in 2024.

And, sadly, last week, we saw the departure of Ncuti Gatwa, the first Black and openly queer man to play The Doctor on venerated British science fiction show Doctor Who. He leaves the program after three too-short years — amid criticisms from some fans that the show’s nods to representation and queer culture made the show “too woke.”

My NPR colleague Glen Weldon penned an awesome tribute to Gatwa’s tenure on the Pop Culture Happy Hour newsletter; read it here. (Have to say, I’m not quite buying Gatwa’s very diplomatic statements that his departure in this moment was “always the plan.”)

Will they be succeeded by shows similarly focused on non-white people? Or will critics like me be forced back into counting heads in cast photos and examining magazine covers to see if any backsliding has occurred?

There are a few truisms about diversity and TV that have remained true over the years, despite Hollywood’s persistent effort to forget them.

Turning around systemic marginalization requires specific effort. This was something I struggled to get producers in Hollywood to admit, back in the days when the lack of representation in major TV projects was so obvious, it was embarrassing. You have to think and talk openly about how diversity is reflected in projects, to make sure it’s top of mind. I still find too many white executives in the industry are uncomfortable with these conversations, which makes progress that much harder.

Setbacks in diversity don’t always result from deliberate bigotry. There’s this psychological dynamic called “moral licensing,” where people believe, because they have done good things, those acts mitigate or cancel the damage done when they do bad things. I call the race-based version of that idea bigotry denial syndrome – where people think they can’t contribute to systemic racism or prejudice because they are not openly bigoted in their everyday life. But that’s where systemic prejudice is most effective – convincing people who would never be directly oppressive to not even see situations where such things are happening.

Here’s a story I wrote for the Tampa Bay Times 12 years ago, illustrating how Bigotry Denial Syndrome was warping the TV industry back then.

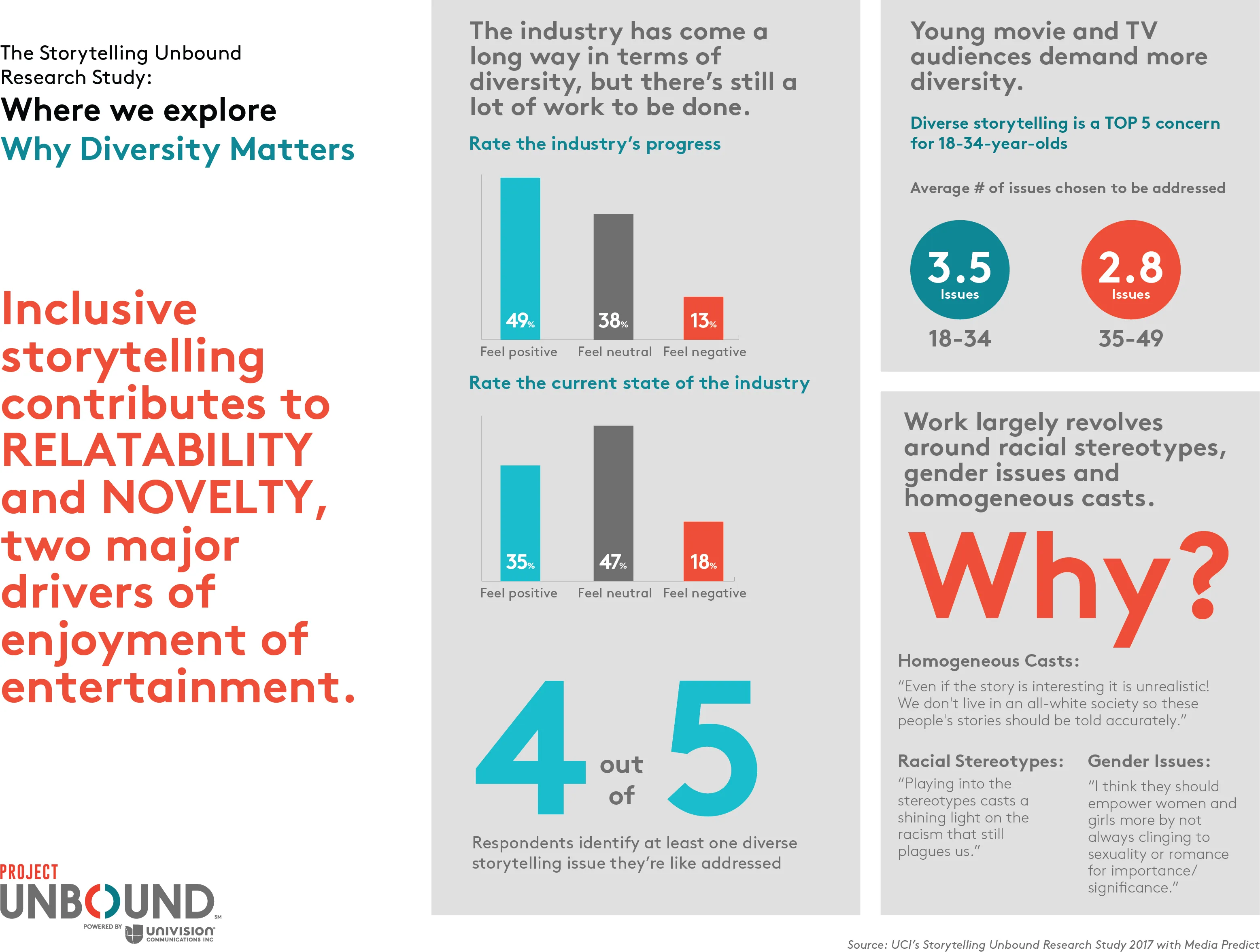

Systemic oppression makes everything worse; equity makes everything better for everyone. Removing systemic oppression makes it much more likely that the most talented, most intelligent, most effective people are on the front lines in every area of society – regardless of their race, culture, gender, sexual orientation or immigration status. And in TV, an industry where there are a wide range of shows with a great spectrum of lead characters means more work for everyone – and, as studies from UCLA have shown, more profitable projects.

Yes, I’m advocating on these issues because I want my kids and people who look like me to enjoy a TV landscape which respects and reflects their experiences as much as anyone. But I also know, in expanding to feature everyone who deserves it, the industry itself will become more creatively and financially successful.